The gender pay gap is nowhere as vast in society as it is in the soccer world, says national goalkeeper Almuth Schult. Good news though: more and more national associations are changing this. Unfortunately there are bad news too: the German Football Association (DFB) is not. Nevertheless, there is currently more movement on this topic than there has been for a long time.

By Mareike Graepel, Haltern

The national team almost won the European Championship. Each team member would have received 400,000 Euro. Oh, no, wait – it was the women who lost 2:1 to England in the final. They would have received 60,000 Euro each. The men would have received six times that amount if they had become European champions in 2021 instead of the Italians. How can that be?

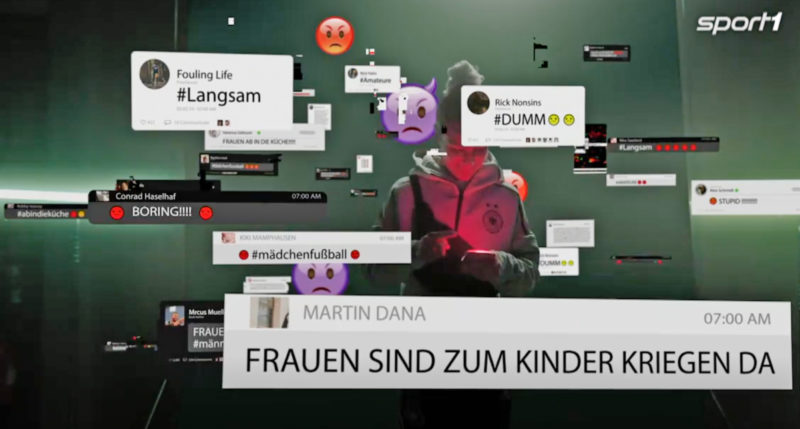

Well, basically because there are historical, organisational and financial reasons behind that. There is a lack of marketing, social perception and non-equal leadership in clubs and associations. Yes, the European Championship has (just) done a lot for public interest in women playing football, but a lot is also happening in the background.

“Do you actually know my name?” The captain of the German national football squad looks directly into the camera, addressing the viewer. Until a few weeks ago, the answer in most cases would have been almost certainly: no. If Manuel Neuer was pictured, viewers would surely know who he is and what he does. It is a provocative promotional film from 2019 in which Alexandra Popp and her colleagues tell us that the DFB women have won the European Championship eight times. The men, meanwhile, have won the same title, uhm, three times.

In 1989, when they won their first title, the prize was a – wait for it – coffee set. Cups and saucers instead of money. The men were awarded 10,000 German marks per head when they won the European Championship for the first time in 1972. The women’s film ends with a clear message to all critics, and a double entendre: “We don’t need balls, we got ponytails.” (“Ponytails” could also be translated into the slang word for horse penises.) The rules are the same – the ball is round and a game lasts 90 minutes – but that’s where the similarities in soccer end: Only twelve associations out of 211 worldwide pay female international players the same bonuses as male international players at major tournaments.

Norway leads the way, others follow suit

The first was Norway in 2017, and only recently Ireland, the USA, the Netherlands and Spain made similar changes – often made possible by the men waiving their full bonuses. That’s not happening with the DFB. Many of the German female footballers, including those in the first and second federal league, the Bundesliga, have to pursue a career outside of sport, train during their free time and often have to take time off work to travel to international matches. Some work for their team’s sponsor, as is the case in Wolfsburg, for example. That helps a bit.

Others are still studying and writing their master’s thesis on the plane to the game in Israel, as the ARD documentary series “Born for this” shows. Viewers are given an insight into the training and lives of the national team players – setbacks, injuries, disappointments, elation, qualifications and successes, just like their male colleagues. The women also play for Bayern Munich, Eintracht Frankfurt and Hoffenheim. Some at Chelsea, Aston Villa and Everton.

But there is only one club out of 326,000 known to FIFA worldwide where there is complete equality: Lewes FC in East Sussex, England. Five years ago, the club was on the verge of bankruptcy. It was saved by its own fans, who now all own a piece of the club. Together, they have decided that all proceeds should be distributed equally to the players. “But it’s about more than equal pay,” says manager Maggie Murphy in the ZDF sports studio. “Both teams play on the same pitch, use the same facilities and have an identical marketing budget.”

This is not the case at any of the German football clubs – in many cases, training times are not only based on the women’s bread-and-butter jobs, but also on when and where the men – the “professionals” – want to train. According to FIFA, a professional is “a player who has a written contract“ and who receives more money for his “football activity than his expenses”. All other players are considered amateurs. National coach Martina Voss-Tecklenburg explains: “Part of the truth about equal pay is that the marketing revenues of men and women, which also result in tournament bonuses, are extremely far apart. Unfortunately, this is still a fact. We at the DFB are working at all levels to optimise this – especially in terms of marketing and visibility.”

What happens in other countries will be closely scrutinised. However, it is also important to the coach and former international: “Before we talk about equal pay, we must first ensure equal play: It must not depend on gender how intensively and qualitatively I am supported as a talent and what framework conditions I have in the clubs. No female Bundesliga player should have to work on the side, we need full professionalism and the best conditions for all players at all levels so that they can concentrate on their sport and develop further.”

Women’s football was banned until 1970

“The European Championship might show the sceptics that our sport is great,” says Maggie Murphy. Gaby Papenburg, one of the founders of the “Fußball kann mehr“, “Football can do more”, movement, agrees. She believes that football played by women is currently experiencing “a real wave” – just like in the stadium when La Ola waves through the oval. Although there are still far fewer public viewings, hardly any car parades and fan miles, viewing numbers of 18 million people like during the final against England prove that there is a whole new level of interest. And that’s not even counting the people who watched online.

The decisive factor is on the pitch: more cameras are now being used for broadcasts of matches such as the European Championship. “If you only show two angles instead of 20, you slow down every game on the screen,” explains national goalkeeper Almuth Schult in the “Ball you need is love” podcast by radio presenter and stadium announcer at Werder Bremen, Arnd Zeigler, explaining why the ARD sports programme, for example, often gives the impression that it is not such an exciting and dynamic game when women play. “It would be nice if more fans in Germany would give it a chance,” says Schult. “And if no one would say: ‘It’s not a tradition.’ How can it be a tradition if it was banned for years?”

The women however have lacked more than 25 years of professional organisation. In 1955, the DFB decided to ban women’s teams from playing football. “This martial art” was “essentially alien to the nature of women”, the reasoning stated, and “in the fight for the ball”, “feminine grace” dwindled and “body and soul” inevitably suffered “damage”. The “display of the body” violated “propriety and decency”. The ban was lifted in 1970, but it would be another twelve years before the first women’s national team was formed.

Damit sich grundlegend etwas ändert, gibt es ganz konkret acht Forderungen für mehr Frauen im Fußball. Darunter verbindliche Quoten für Fußballverbände von mindestens 30 Prozent Frauen in Führungspositionen und in Aufsichtsräten sowie die Besetzung eines jeden Vorstandes bzw. Geschäftsführung von allen Profiligen mit mindestens einer Frau, ein paritätischer Unterbau von Frauen und Männern auf der zweiten Führungsebene bei Verbänden und Clubs – alles bis 2024.

The “Football can do more” movement

Another 40 years later, the “Football can do more” movement finally wants equal rights at all levels. The campaign was launched by professional players such as Almuth Schult, referees, commentators, chairwomen and managing directors of fan organisations and associations. Co-founder Gaby Papenburg says: “There is a lot of hype at the moment. We helped set off this current wave of interest – we don’t have to be modest about that.”

Two staff appointments are far from being a victory, but they are an important step: Donata Hopfen has been Managing Director of the German Football League (DFL) since the beginning of January 2022, while Heike Ullrich is the new General Secretary of the DFB. “It would be great if we could now get to a point where women no longer have to take the long route vie the hurdles in the administrative process to pursue a career,” says Gaby Papenburg.

To bring about fundamental change, there are eight specific demands for more women in football. These include binding quotas for football associations of at least 30 per cent women in management positions and on supervisory boards, as well as the appointment of at least one woman to every board of directors or management board of all professional leagues and equal representation of women and men at the second management level of associations and clubs – all by 2024.

Isn’t that pretty ambitious? Papenburg says that if she doesn’t build up pressure, nothing will happen. Targeted programmes to create equal opportunities for women in sport-related areas in the clubs are to be created for coaches, scouting, youth development centres, coaching licences and management programmes. And the issue of money is also included in the demands: There should be equal pay for the same job at every level of the hierarchy.

This includes changing the framework conditions that strengthen women and diversity in the organisation. More focus is also required on recruiting, personnel development, career planning, female mentoring programmes, work-life balance regulations, part-time management and infrastructure in the workplace. Gender-equitable, non-discriminatory language at all levels of football is just as important as the consistent sanctioning of all forms of sexism and discrimination, including off the pitch.

Children and a career in football

The German Soccer Association, on the other hand, sees its “Women in Football Strategy FF27” as a sufficient basis for action at all federal, state and regional levels. Specifically, this means that by 2027, the national teams and the clubs in the women’s Bundesliga should have won international titles, the number of active female players, coaches and referees should have increased by 25 per cent and the media reach across all platforms should have doubled. It is also planned that by then the proportion of women in DFB committees and full-time management levels will be at least 30 per cent.

Since the end of the 1980s, two national team players have had children during their active careers. Martina Voss-Tecklenburg, the current national team coach, and Almuth Schult. Arnd Zeigler wants to know from the goalkeeper, who is now moving from Wolfsburg to Los Angeles to join Angel City FC, whether she would rather be called a mother of twins who plays football or a Soccer player with two children.

She replies: “Basically it says the same thing, but I would be happier if it wasn’t an issue with the being a mother at all, but that there are simply more mothers who play football. I hope that I have encouraged or can encourage one or two girls to take this step. And not let someone else make the decision for them.”

The small number of children born to active female national team players is drastic proof that men do not even have to interrupt their careers ever so briefly to plan a family. After all, there are no statistics on how many male national team players fathered children in recent decades. What is known, however, is that during the 2018 Men’s World Cup, the public debated whether pre-match sex is harmful or beneficial.