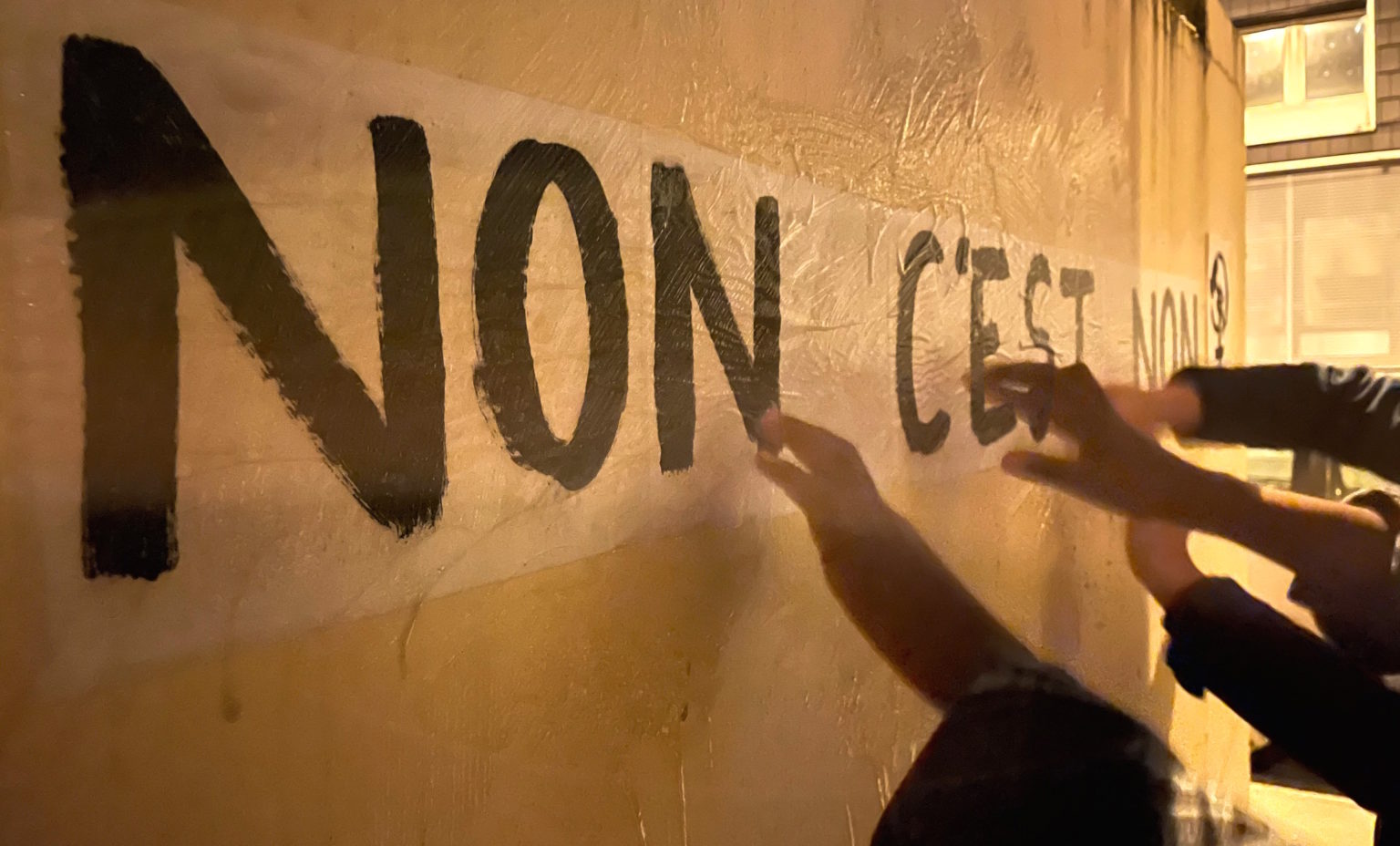

Slogans like “No means no” or “Abortion is a right” are emblazoned on the walls of many houses in France. They are put up by activists who go around the houses at night with self-painted letters on paper, and glue. Their actions are not entirely legal. But anger justifies the means, they say.

By Carolin Küter, Lyon

It is a Tuesday evening, shortly before midnight. Lola* is standing in a quiet side street in front of a smooth balcony wall of a raised ground floor flat in a new building. Lights are on inside, otherwise only street lamps illuminate the darkness. The young woman carefully smoothes out an A4 sheet of paper stuck to the balcony wall. A black “U” stands out clearly against the white paper. Lola takes a step back. Next to her stand three other young women: Raphaëlle, Malo and Maxime. They look proudly at their work: “Jesus had two fathers” is now emblazoned on a row of sheets glued to the wall. The residents of the flat have not noticed. They will probably be surprised in the morning.

The four women are part of a collective that puts feminist, anti-racist and anti-queer messages on the walls of houses in Lyon in south-eastern France. “Jesus had two fathers” is an allusion to the ultra-conservative protest movement “Manif pour Tous”, meaning “rally for all”, founded in 2013 against the introduction of gay marriage. Slogans like “We believe you”, directed at victims of sexual violence, or the anti-police abbreviation “ACAB” are also part of the repertoire.

There are similar groups all over France. According to their own information, there are a few hundred activists in Lyon, but the fluctuation is high. Most are between 18 and 40 years old. Cis men, thus men who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, are not allowed. The collective wants to be a protected space for women, transsexuals and non-binary people who do not feel they belong to one gender.

Lola and her comrades-in-arms met at Gabriell’s today before their midnight tour to make the banners. Since 9 p.m. they have been sitting in their** flat-sharing room, painting black and red letters on white pieces of paper. The hallway is full of clothes dryers on which the papers are lying to dry. Lola is leafing through a folder. “I’m looking for something on the subject of childlessness,” she says. Next to her squats Maxime, who is writing “No means no”.

Then there is Raphaëlle, who sets about painting a slogan for rape victims: “Whether I sue or not, both are my right.” Victims are often told by those around them that they should go to the police, she says: “But everyone has to decide that for themselves.” “And as if that would help,” Malo interjects. According to government calculations, the conviction rate for reported rapes in France is one percent.

The activists here are between 19 and 28 years old. Gabriell studies music, Lola politics, Malo is a graphic designer, Maxime and Raphaëlle work in the social sector. What unites them is anger. Anger that results from personal experiences they don’t want to talk about. Anger that they, like Gabriell, are discriminated against as transsexuals and get harassed on the street, that women do not have equal rights in politics, that prominent men accused of rape continue to have careers.

For example, director Roman Polanski, who admitted to raping a minor, who was accused of sexual violence by eleven women – and who received the most important French film award, the “César”, in 2020. Or Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, who was still being tried for rape when he took office in 2020.

Rape allegations against ex-ministers

Recent rape allegations against former news anchor Patrick Poivre d’Arvor and former Environment Minister Nicolas Hulot caused a stir – and Emmanuel Macron’s reactions to the allegations against Hulot. The president said it was good that sexual violence was being discussed, but that he did not want an “inquisition society”. Last but not least, activists are angry about police violence that too often goes unpunished – as in the case of Adama Traoré. The 26-year-old black man died in police custody in 2016. Since then, the judiciary and the family have been arguing about who is to blame.

The activists want to vent their anger and make their demands heard. Lola, Maxime and Malo are taking part in the sticker mission for the first time today. She saw the slogans in the city, was impressed and got in touch with the collective in Lyon via social media, says Lola. “It’s something concrete that you can see,” says the 22-year-old. “Writing is the most effective tool,” says graphic designer Malo. “It gets you straight to the point.” The messages are meant to shock, to trigger a surprise effect – such as “Daddy killed mommy”, an allusion to femicides, of which there were 102 in 2020, according to the Ministry of the Interior.

Through their actions, the activists feel they are reclaiming the public space where they so often feel harassed. “We reverse the balance of power,” says Gabriell and tells of an action in Dijon: a woman had been raped by a Tinder date. Activists from the city then arranged to meet the man under a false pretext. At the meeting point, a wall read “Rapist, we see you”. “It’s a big hit,” Gabriell said.

The fact that their actions take place on the edge of legality does not bother the collective. Pasting on public walls is considered minor damage to property; in the worst case, there is a threat of fines. But that rarely happens, says Gabriell: “For us, it’s civil disobedience.” And they consider this is appropriate in view of a society that does too little to protect women, trans and non-binary people.

Activism with simple means

When enough slogans have been prepared to be able to get down to business, Gabriell stirs the glue with a hand blender: Flour, water and a little sugar. The liquid almost looks like cake batter. In the collective, there is a story about glue users in Paris who got caught by the police and excused themselves by saying that they were on their way to a crêpe evening, Gabriell says mischievously. Equipped with the bucket of glue, hand brushes to spread the glue and a folder with the letters, Lola, Malo, Maxime and Raphaëlle set off on their night tour of Lyon. Gabriell doesn’t come along so that the group doesn’t get too big.

One of their first stops is a wall behind a bus stop. The four women go to their posts: Maxime spreads the paste, Malo sticks the letters on, Raphaëlle smooths them out and Lola stands guard at a nearby intersection. The slogan of choice: “Forests, our legs, walls, let’s shave nothing any more.”

“Shaving the walls” in French means walking as close to a wall as possible in order not to show oneself. After a few minutes, the slogan is written in big black letters on the wall. The activists comment “Super” and “Unbelievable”. They high-five, form a group again and turn the corner of the building. The next free wall is already waiting.

*All names have been changed to protect those named from prosecution.

** Gabriell defines as non-binary, i.e. neither a woman nor a man. The pronoun “they/them” is used here as a singular pronoun.