In a country where women are still often disadvantaged, Chiaki Mukai and Naoko Yamazaki have come a long way: they are Japan’s only female astronauts. This is the story of two women and their sky-high journey against all odds.

By Eva Casper, Kyoto

Getting to the top is not easy for women in Japan. In a country where power and money are still mainly in men’s hands, women who have a career are the exception. And it is even more unusual that they make history in the process. Chiaki Mukai and Naoko Yamazaki have done just that. Of the twelve astronauts Japan has trained so far, they are the only women. They grew up in a time when inequality in Japan was worse than it is today and have pursued their dream against all odds.

Chiaki Mukai was born in 1952 in Gunma, a prefecture north of Tokyo known for hot springs and ski resorts. Her parents had always told her how important it was to have a good education in order to earn money: “I shouldn’t be dependent on anyone.” In Japan in the 1950s, that’s an unusual attitude – much like in Germany at the time.

It was common for women to marry and have children instead of working for a living. Already as a girl, Mukai was passionate about science. She loved to watch animals, to catch small fish and lobsters and to raise them at home. She learned to ski and competed as a student. Then she realised that she was faster than some men.

The only woman in the team

Mukai has often been one woman among many men. She studied medicine at Keio University in Tokyo and then worked as a doctor. In 1983, she learned that Japan wanted to train its own astronauts for the first time and applied for the program. She explains: “I wanted to expand my horizons and see the Earth from space.“ A long, complex selection process followed. One of the most famous tests is probably the human centrifuge. In it, the apparatus spins faster and faster around its own axis, the blood rushes to the human feet. “If that doesn’t make you sick, there’s something wrong with you,” Mukai jokes.

In the summer of 1985, at the age of 33, Mukai was finally selected as one of three candidates. But it would be another nine years before she actually could go to space. Just under six months later, on 28 January 1986, the space shuttle “Challenger” exploded shortly after take-off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida – all seven crew members were killed. To date, it is the worst accident in the history of US space travel. “I was shocked,” Mukai says. Nevertheless, she did not think about quitting. After all, 100 per cent safety cannot be guaranteed.

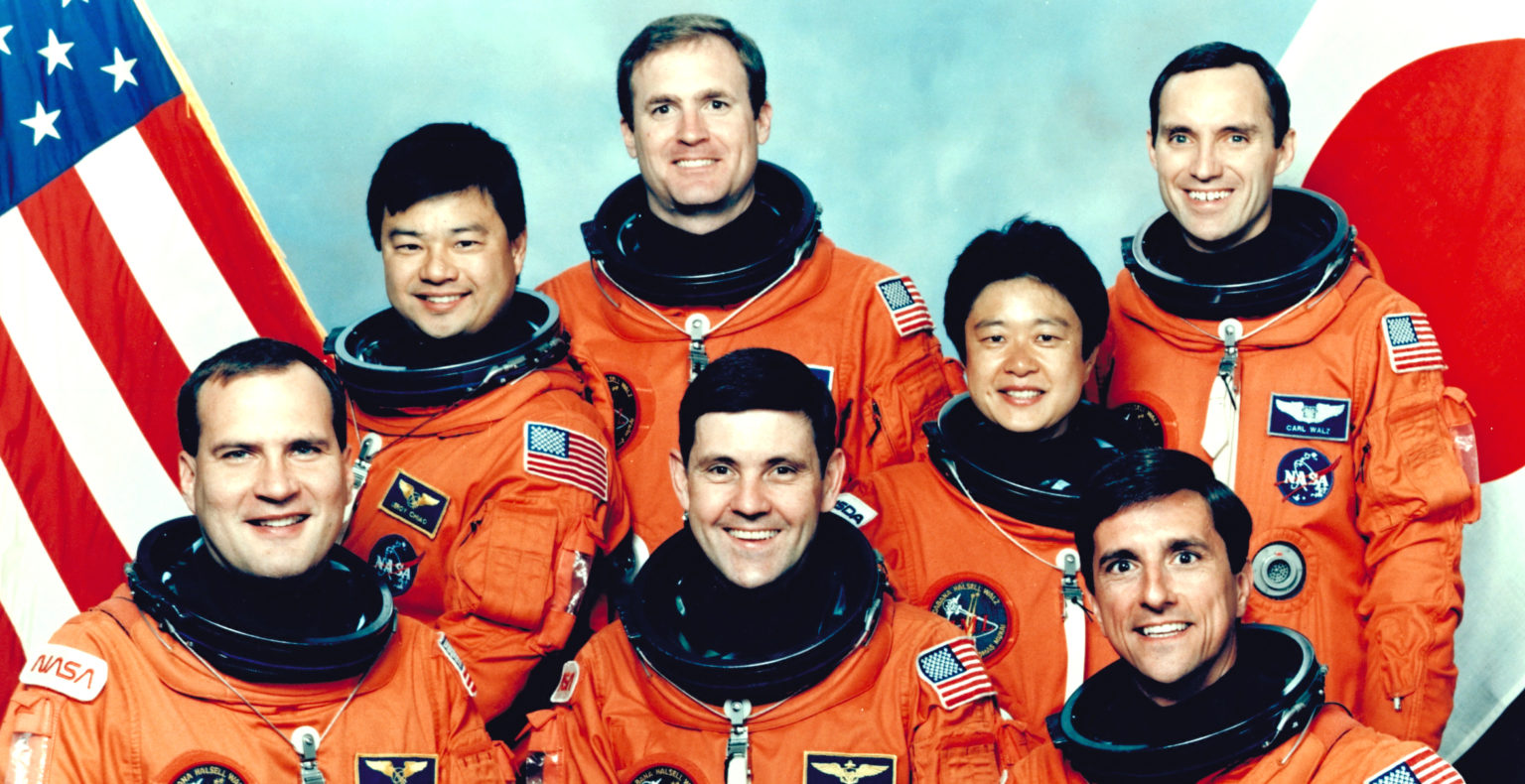

In 1994, Mukai finally set off on her first flight into space: with the international STS-65 mission – as the first Japanese woman ever and the only woman among six men. At press conferences, many ask what it’s like to be the only woman on the team? “Wonderful, I’m the prettiest one on board,” she jokes. When Sally Ride became the first US woman to go into space in 1983, she was asked to answer whether being in space would negatively affect her ability to have children or whether she would cry on the mission if something went wrong. Mukai says she was never asked such questions. However, she was already 42 when she started her journey.

Research in space

In fact, reproduction was part of her research. Using fish, she investigated what effects weightlessness has on the body. On her second mission in 1998, she was again the only woman. The nine-day stay in space was also about finding out what effects weightlessness has on people in old age. Astronaut John Glenn was on board for this. The astronaut, 77 years old at the time, set the record as the oldest person in space.

Not until 2021 was this record broken, first by Wally Funk and then by 90-year-old William Shatner, known as Captain Kirk from Star Trek. Today, astronauts often spend several months in space. Their bodies get used to gravity and their muscles regress. They miss their families and friends. After setting up a daily routine, they have free time to fill.

It was different for Mukai. Her longest stay lasted two weeks, during which she and her team conducted hundreds of experiments. Most of the time, she was so exhausted that even the unaccustomed sleeping in weightlessness did not bother her. But as often as time allowed, she looked at the Earth. Looking back, she says: “No matter how long you look, you always want to see more and more.“ But what impressed Mukai most was the return to the planet.

As she sat in the space shuttle, she felt gravity kick in again. It was as if someone was standing on her shoulders and pushing her down, she says. Back on Earth, she couldn’t walk straight at first. Everything felt heavy, even a business card. This feeling lasted for three days. On the last night, she preferred not to go to bed. She felt she would lose this feeling by the next day. “It was like the little mermaid coming out of the depths of the sea and seeing the sun for the first time,” Mukai says, “everything was very new to me.”

After her journeys into space, the now 69-year-old works in research and teaching, including at the International Space University in France and for the Japanese space agency JAXA. Since 2015, she has been Vice President of the Tokyo University of Science. There, she also heads the so-called “Space Colony Research Center” – an organisation founded five years ago whose goal is to develop technologies that are useful in space, but also on Earth, for example to enable the cultivation of vegetables, to save water or to generate electricity.

Astronaut and mother

While Germany has yet to send a female astronaut into space, in 2010 Naoko Yamazaki became the second Japanese woman to fly to the ISS for 15 days as part of a US team on the STS-131 mission. As an engineer, the then 39-year-old operated a robotic arm. Unlike Mukai, Yamazaki is a mother, which is why the press nicknamed her „Mama-san“. “San” corresponds to the German pronunciation for Mr and Mrs. But Yamazaki does not like the name. Men, she says, do not get so reduced to being a father. Yet the universe is a pretty equal place, Yamazaki thinks. Mukai also reports that she never felt discriminated against when working in the team.

The fact that Yamazaki became an astronaut is also due to the many role models who encouraged her to take this step. Already as a child, she enjoyed watching science fiction films and reading comics. At that time, it never occurred to her that she could become an astronaut herself. That changed when the Challenger crashed. Yamazaki was 15 years old at the time. Christa McAuliffe, who had participated in NASA’s Teacher in Space programme, also was among the victims.

Yamazaki was encouraged by the thought that even a teacher could become an astronaut. She decided to study space technology at Tokyo University. Back then, if she told anyone about her career aspirations, people thought she was joking. “Even my parents,” she recalls. But in 1999, Yamazaki was selected as an astronaut. It took another eleven years before she actually went into space.

Earthly challenges

This time, too, a tragic accident intervened: The crash of the space shuttle “Columbia”. Her daughter was not yet a year old at the time and Yamazaki feared that it was too dangerous. “I wanted to go into space, but I didn’t want to sacrifice my family.” Eventually she felt: Her desire was greater than her worry. And: Those who want to go into space as parents have to live with the same earthly challenges as others – balancing family and career. This usually leads to women staying on Earth.

What many people don’t think about is that astronauts not only travel in space, but also have to complete long training sessions – often abroad. Yamazaki explains that it was only possible to combine the two because her husband at the time quit his job and took over childcare. A model that is very unusual, in Japan and elsewhere. She was criticised for this in the media. It was said that she had abandoned her child. Conversely, when she said she wanted to take a break from training to look after her daughter, she was reminded of her training being financed by taxpayers’ money. In short, whatever she said, there was criticism.

To make it easier for women, gender stereotypes have to be overcome, Yamazaki says. Many girls would be enthusiastic about space, but there is pressure from society that science is not for girls. Yamazaki herself attended an all-girls school. There, it was normal to be interested in science. And the teachers were a role model for her.

Today, Yamazaki is president of the Young Astronauts Club, which aims to encourage girls to pursue careers as astronauts. She also co-founded the Space Port Japan Association in 2018, which wants to build Japan’s first launch pad to launch rockets for tourists into space. When she was on Earth, Yamazaki says she thought space was very special. But when she got there, Earth seemed to her “a very admirable place in the infinite vastness of this darkness”.