Máxima Acuña de Chaupe from Cajamarca in Peru has been fighting for years against the Yanacocha gold mine because its owner wants to buy the land on which the indigenous smallholder lives. Despite all the threats from the mining company, she is still holding on to her piece of land. She was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her resistance.

By Eva Tempelmann, Lima

High up at an altitude of 4,000 metres in the Peruvian Andes, five hours from the city of Cajamarca, a small house stands crouched in the treeless plateau. This is where the indigenous smallholder Máxima Acuña de Chaupe lives with her family. There are several lagoons nearby – important sources of water for the region. Alpacas graze near the house. Apart from the wind, not a sound can be heard. An idyllic scene, you might think.

But a huge new gold and copper mine is to be opened in this wild landscape. “Conga” is the expansion of the existing Yanacocha mine in Cajamarca, the largest gold mine in South America and one of the largest and most profitable in the world. It is largely owned by the US company “Newmont”; the Peruvian “Buenaventura” and the World Bank are also shareholders. The open mine stretches for around 250 square kilometres across a formerly green landscape. The ground has been torn open and large machines dig up to 500,000 tonnes of rock every day in search of the coveted precious metal.

“We will have no future with mining on our doorstep,“ says Máxima Acuña de Chaupe about the conflict. In recent years, the petite woman with the long plaited braids worn by local women in the Andean highlands has become a symbolic figure of resistance to mega-mining in Peru. Since 2011, Acuña has been fighting against the mining company “Newmont”, which wants to buy the four hectares of land on which the 48-year-old lives with her family. Her land is in the centre of the area where the gold is to be mined. A battle like David against Goliath. And a legal dispute that symbolises the alliance between the government and the company – and the lack of rights for the civilian population.

Mining instead of development

The Yanacocha gold mine has always been controversial. For some, the Peruvian government and the mine’s shareholders, it represents a business worth billions. But the majority of Peruvians look on in horror at the irreparable destruction of their region and their livelihoods. The biggest conflicts centre around the most precious of all commodities: water. The problem with the gold mines is that vast quantities of water are needed and polluted during the extraction process.

The process water is then contaminated with heavy metals and chemicals – including lead, mercury and arsenic – and discharged back into the rivers. The contaminated sites that remain after the end of mining activities are ticking time bombs. There are thousands of them in Peru. Neither the mining companies nor the government feel responsible for dealing with these highly toxic residues. Worse still, the environmental and social standards for mining have been repeatedly lowered in recent years.

“The assumption that mining is a driver of the local economy has turned out to be wrong in Cajamarca,” says Gloria Alvitres from “Red Muqui”, a network of environmental and human rights organisations based in Lima. It supports and advises rural communities affected by mining and works with allied representatives on political alternatives. “The fact is: After 20 years of mining, the Cajamarca region is still one of the poorest in the country,” says Mirtha Vásquez from the non-governmental organisation “Grufides”, a member organisation of “Red Muqui”. She adds: “Many people hoped for jobs and instead lost their livelihoods.”

Attacks by mining companies

Mirtha Vásquez is a lawyer and has been advising smallholder farmer Máxima Acuña de Chaupe since the beginning of her legal dispute with the US company Newmont. It is an exhausting task and there is no end to the legal dispute in sight. The dispute revolves around a few hectares of land under which lies the coveted gold that the company wants to mine. The company has already bought up 5,400 hectares around the village of Sorochuco for the planned Conga project since 2010. However, Acuña rejected Newmont’s offer. The reason: like 60 per cent of the population in the area, she lives off agriculture.

Potatoes, yucca, wheat and oats grow on the fertile soil. She uses the rest of the land as pasture for her cattle. “I was born and raised in Sorochuco,” she says, “I bought my land in the hope of spending my whole life there.” So she stayed. “Newmont” did not put up with this. Mining personnel soon turned up, backed up by police in uniform. There were death threats, beatings, their livestock disappeared or was killed. The attacks on her farm were not punished. On the contrary: although Acuña holds a title deed to her land, the company sued her for breach of the peace.

When the company’s violations increased – her house was broken into and her family was beaten up – Máxima Acuña de Chaupe went to court. Three years later, the Supreme Court in Cajamarca ruled in favour of “Newmont”. Acuña de Chaupe and her family were sentenced to two years and eight months’ probation and fined the mining company the equivalent of 1,500 Euro. No rarity in a country where even the judiciary is steeped in corruption.

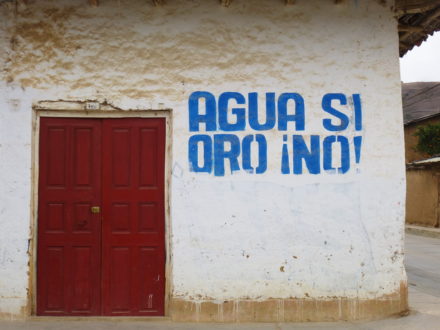

“You can’t drink gold“

The judgement caused great consternation among the Peruvian and Latin American public. Expressions of solidarity proliferated on social networks, demonstrations were held in Lima and open letters were sent to the government. “Agua sí, Oro no!”, translated as “Water yes, gold no!”, people shouted on the streets, as well as “You can’t drink gold!” The dispute between the smallholder farmer and the large corporation symbolises the big question of whether the right to clean and sufficient drinking water is really guaranteed in Peru. “Water means life,” says Máxima Acuña de Chaupe, “we can’t just sell it to a company.”

Due to the huge public pressure, the Conga project was finally suspended indefinitely and Acuña was acquitted of all charges in the second instance. But the harassment by the company did not stop. On one occasion, security forces destroyed extensions to the family’s property, on another, security cameras were installed within sight of the house.

At first glance, it seems that Acuña is not intimidated by this. But the years-long legal dispute is sapping her energy. “Máxima is often on the verge of exhaustion,” says lawyer Vásquez about her client. “The constant surveillance, the assaults – I often wonder where she gets the strength to put up with it.”

For her resistance and commitment, she was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco in April 2016, which is considered the most important international award for environmental activists. A satisfaction for sure. At the award ceremony in San Francisco, Acuña refrained from making an acceptance speech. “I am a woman from the mountains,” she sang instead in her native Quechua language. “I defend the lakes and the land, I am not afraid.”

But the public honour has made the smallholder even more of a target for her opponents. A few months after receiving the award, Acuña was once again attacked by employees of the company. “Initially, we were seriously worried that she would suffer the same fate as Berta Cáceres,” says Vásquez. Cáceres had been awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize the previous year because she had campaigned for indigenous rights in Honduras for years and protested against the government and oligarchs in her home country. She was murdered in March 2016.

No room for criticism

The power of the big players is also unevenly distributed in Peru. In a study, the Society for Threatened Peoples shows that there are problematic cooperation agreements between mine operators and the Peruvian police. On the basis of these contracts, police officers provide so-called “extraordinary additional services” for extractive companies in return for payment. State and economic interests are thus allied against the interests of the local population.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the government has repeatedly cracked down on resistance from the civilian population. In the media, for example, mining critics are defamed as terrorists and opponents of development. The media concentration is too great for alternative opinions to be heard and the conviction that mining is the key to progress is too great. According to the state ombudsman’s office for human rights, almost 100 people lost their lives in violent clashes between residents and mine operators between 2006 and 2016.

Despite all the criticism from environmental and human rights organisations, the government continues to rely on mega mining as an engine for economic development. President Pablo Pedro Kuczynski, who recently resigned from office prematurely due to corruption allegations, has also repeatedly emphasised in public speeches that Peru is a mining country. Meanwhile, the tough legal dispute between Máxima Acuña de Chaupe and “Newmont” is entering the next round.

The company wants to convince the smallholder to make a deal: it is offering money and a house on a new piece of land in exchange for Acuña’s agreement not to lay claim to her previous four hectares of land. But the environmentalist does not want to negotiate. “This is about our rights, not about money,” Acuña emphasises. “I will not be bought.”